Utilitarianism and Deontology Part 3: The Wrongness-to-Goodness Ratio

Part 1 of this series shows that the only difference between those who call themselves deontologists and those who call themselves utilitarians is a subjective and arbitrary line that is drawn. Part 2 provides examples of how utilitarianism and deontology are portrayed (for better or worse) in film.

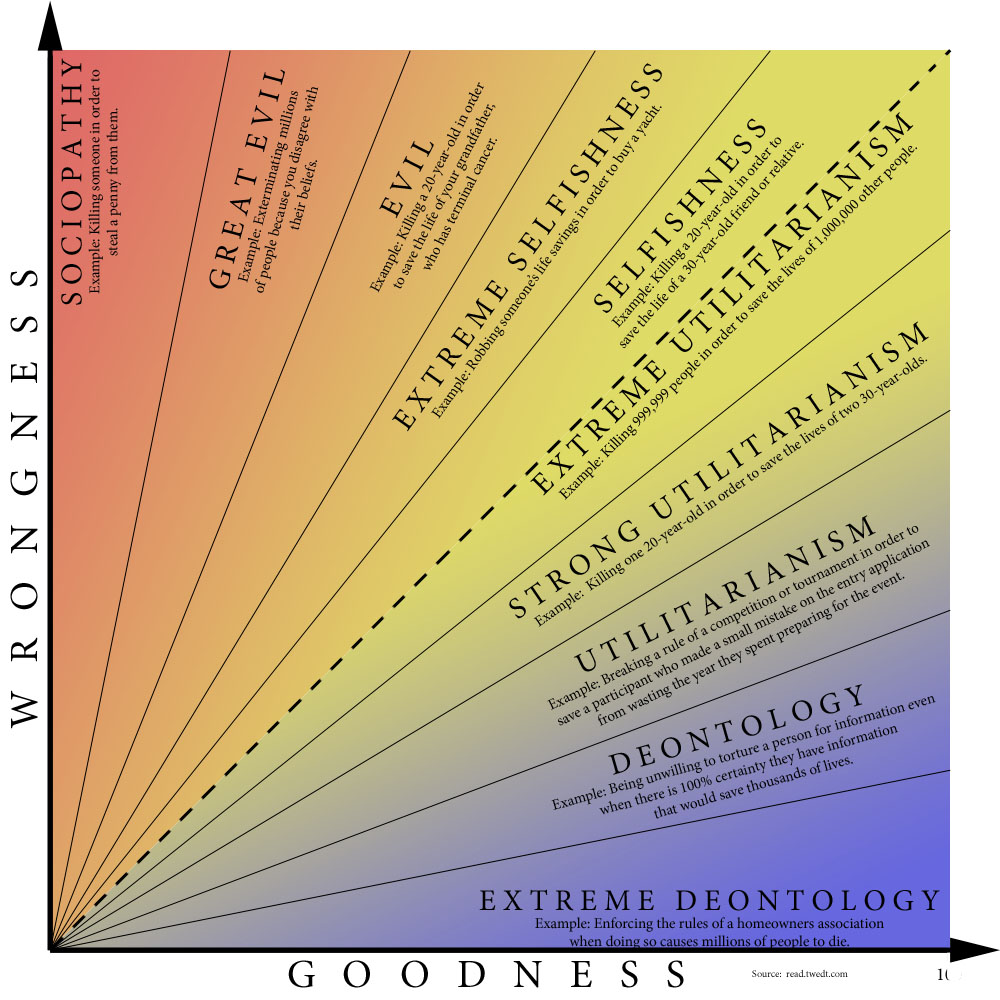

With deontology and utilitarianism being the extremes of a morality spectrum, everyone inevitably falls somewhere within this scale according to the subjective line they draw within the spectrum. Just for fun, we could express this grayness using a Wrongness-to-Goodness Ratio. This is a ratio that every one of us intuitively sets up for ourselves when we must “calculate” our answer to various moral dilemmas.

A strong utilitarian (or weak deontologist) will have a ratio close to one, while a strong deontologist (or weak utilitarian) will have a ratio close to zero. To make this easy to understand, let’s explore the two extremes with examples. Assuming wrongness and goodness can all be measured from 0 (neutral) to 100 (very wrong or very good), we have:

- Strong Utilitarian: Supposing that the killing of an 1,825-day-old child were a 29.99 on the wrongness scale of 0 to 100 (where making the universe cease to exist is 100) and saving a 1,824-day-old child from death is a 30 on the goodness scale of 0 to 100 (where allowing everyone everywhere to be maximally happy for all eternity is a 100), we have that the extreme utilitarian (one who would kill the 1,825-day-old child to save the 1,824-day-old child) demonstrates a wrongness-to-goodness ratio of (29.99 / 30), or nearly one. This person isn’t bothered at all by the personal responsibility of taking a life – it seems to be a completely null factor, which is why this utilitarian can still take action even with such a small margin of gain. It is not possible for a utilitarian’s wrongness-to-goodness ratio to be exactly 1, because that would mean they’re killing even when there is nothing to be gained by the act. By definition, a utilitarian only does wrong when the good that comes from it is perceived to exceed the good that would come from not doing wrong.

- Strong Deontologist – Supposing that allowing a friend to play a pirated copy of a Beatles song were a 0.1 on the wrongness scale, while preventing the universe from ceasing to exist were a 100 on the goodness scale, the person who is only barely able to cope with the guilt of listening once to the pirated copy of the Beatles song in order to prevent the destruction of the universe demonstrates a wrongness-to-goodness ratio of (0.1 / 100), or almost zero. It is not possible for a deontologist’s wrongness-to-goodness ratio to be exactly 0, because that would mean there is no trade-off in doing good. In a scenario that produces a ratio of zero, a neutral action produces a good result – no wrong is committed.

It would be very difficult to pick numbers in the above examples or in any other examples that everyone would agree are truly accurate. But the exact way in which the numbers are scaled (linearly or exponentially like the Richter scale) doesn’t matter. Perhaps an even better way to represent the numbers would be to always define the good result to be a value of 1 and then scale the wrong action accordingly. The point here is to show more clearly how people determine where they are on the sliding deontology-utilitarianism scale.

I leave you with an interesting chart to show exactly how the wrongness-to-goodness ratio works.

Note 1: Regarding Sociopathy and Great Evil, while it may seem strange that robbing someone for a penny is considered more evil than genocide, the focus here is on what is gained. What is more valuable to an evil person: getting rid of all people in the world who disagree with their cherished beliefs, or gaining a penny? In this light, genocide makes more sense than killing someone for a penny, although obviously either action repels any normal person.

Note 2: Despite the dotted line being in the center, a person who acts in a way that places them truly on this line would neither be a deontologist nor a utilitarian. It is the only location on the chart that requires actions be motivated by randomness since nothing is gained or lost through those actions.

(c) 2020 Read Twedt

Leave a Reply