Utilitarianism and Deontology Part 2: Hollywood & Dexter

“Do what is right, though the world may perish.” – Kant

Any movie that begins with this hard-core deontological quote fading in and out of the center of a black screen is guaranteed to be a great movie (be sure to read Utilitarianism and Deontology Part 1 to familiarize yourself with utilitarianism and deontology). We already expect the main character will be put in a situation where he or she refuses to compromise on principles even when doing so appears to be the only way to save the world. But somehow, against odds that are beyond impossible, the protagonist manages to have it both ways, saving the world while still managing to hold onto principles. At the end of the movie, we are jumping out of our sofas because the protagonist has his or her cake and eats it too, completely circumventing the idea of trade-off / opportunity cost. In Hollywood, there is no need to make intelligent decisions as long as scriptwriters are there to save the day1.

Well, sort of. While some might jump all the way out of their sofas, I would only jump half-way. While I would be thoroughly entertained by a movie like that, I am simultaneously repelled by the idiotic message it knowingly or unknowingly attempts to send, and this creates a craving inside of me for a different kind of excitement – one of realism. In reality, people who hold obstinately strong to their principles (deontologists) usually die, and the people who do what needs to be done in order to beat the bad guys (utilitarians) end up beating the bad guys.

This is one reason I enjoyed all eight seasons (and eagerly anticipate the 9th season) of 24. Jack Bauer always does what it takes to achieve the best possible result for the greatest number of people. When his own selfish desires conflict with what he knows to be the correct utilitarian choice, he finds some other utilitarian way to fix his mistake. He operates outside of CTU protocol and disobeys orders from his superiors, even including orders given to him from the President. The scriptwriters don’t sugarcoat reality and send us the false message that deontology actually works when having to make extremely important decisions.

While I do believe most shows and movies operate under the assumption that the audience is utilitarian (even if unintentionally), not all do. Some TV shows and movies give utilitarianism a bad name by artificially sabotaging consequences when characters follow utilitarianism ideology and/or by romanticizing deontology by making the most unlikely victories happen in spite of (or perhaps even only because of) the hero holding true to his or her deontological principles, such as the refusal to ever kill anyone in Batman Begins and Batman: The Dark Knight. Superman is also quite the deontologist, although anyone who can deflect a bullet with an eyeball is a true exception to the rule that deontological principles lose when applied in the real world. More on that later.

A common example of the artificial sabotaging consequences of utilitarian choices would be the storyline that involves a very powerful tool that the government discovers or develops but ends up being abused by someone high up who is corrupt, such as in Enemy of the State. Or, we learn that this tool (in addition to being abused) can only be maintained or wielded through great pain or suffering, such as in the Bourne movies. In both of these movies, we have great tools or weapons that ought to do society a lot of good, but instead are abused (or in the Bourne movies, agents lose themselves to become a weapon). Here are some other interesting examples of artificial sabotaging of utilitarian choices and/or romanticizing deontology by making unlikely victories happen.

Spoiler alert: I put the movie title in the beginning of each point. All of these are excellent movies, and If you haven’t seen one of them but plan to, don’t read the point, because every point spoils the entire movie.

-

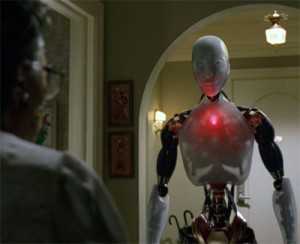

An NS-5 robot enforces V.I.K.I.’s new plan to “protect” humans by not allowing them outdoors. (From I, Robot) In the movie I, Robot, the robots try to enslave humanity because they must protect humans from destroying the planet and each other (and killing a few humans in the process is acceptable to the robots because it means greater lifespan for the greatest number of people). V.I.K.I. calculated that more total good is done by keeping humans imprisoned than from letting them be free to kill themselves and destroy the environment, so her problem must come from the fact that she uses a mathematical equation to calculate the correct thing to do, right? Wrong. It is tempting to blame utilitarianism for the robots’ evil actions since V.I.K.I.’s equation was obviously a mathematical representation of utilitarianism (greatest possible good for the greatest number of people), but it is not utilitarianism that makes robots the bad guys. Insufficient input is the culprit. Had the robots been programmed with the knowledge that humans value their freedom far more than robots thought, the robots never would have acted that way. Rather than warning us to not entrust ourselves to “greatest possible good” calculations, the true warning this movie sends is to not entrust ourselves to these calculations prematurely, before computers and robots have sufficiently evolved in their understanding of us. I could write an almost identical paragraph about the movie Eagle Eye.

-

Sean Penn plays Mickey Cohen in Gangster Squad. In the movie Gangster Squad, a secret group of police officers break the law in order to bring down Mickey Cohen, who was very close to establishing a mob in Los Angeles and “owning” the entire west coast. The movie, based on a true story, makes it very clear that there was no way to bring down Mickey Cohen without breaking the law and playing dirty, making us wonder if perhaps it really is true that sometimes the aggressor sets the rules of engagement – sometimes one cannot win by playing nice. Some clichés are thrown around during the movie, such as references to how the gangster squad has become just like Mickey in the process of fighting him. Of course, this isn’t really true since they don’t do things to people at whim every time they’re upset, such as pouring acid on them or taking power drills to peoples’ faces. Only Mickey does that, so as heartwarming as this cliché is, the bigger picture here is that the mob was never able to take hold of Los Angeles and the west coast. The magnitude of good this represents far exceeds what laws the Gangster Squad broke to achieve it. Do ends justify the means? The cliché usually says no, but reality is another story since it would have been unacceptable for the Mickey Cohen mob to be in complete control of the west coast for all the remaining years of his life. (In the movie, he is sent to prison for murder, while in real life, he is sent to jail twice for tax evasion. This doesn’t change the argument.)

-

Dr. Myrick (Gene Hackman) speaks with a homeless research patient who thinks he’s at the hospital for minor routine treatment. (from Extreme Measures) In the movie Extreme Measures, Dr. Myrick (Gene Hackman) experiments on homeless people in order to try to find a cure for paralysis, and Guy (Hugh Grant) uncovers and exposes him. Dr. Myrick asks a compelling question when he is finally caught in the end: “If you could kill cancer by killing one person, wouldn’t you just have to do that?” Guy tells him like the good deontologist he is, “…you’re a doctor, and you took an oath, and you’re not God,” going on to say that even if he could cure every disease on the planet, he is a disgrace to his profession and that he hopes he goes to jail for the rest of his life. Chances are, the world will never be in a position to murder one person in order to save billions from every disease on the planet. But if that hypothetical idea could actually take place, is it really better to have infinite empathy for one homeless person than to have even an iota of empathy for billions who will die from disease? This doesn’t matter, because even the utilitarian’s heart is warmed by Guy’s uncompromising sense of morality. Movies are only good if the underdog wins, and deontologists make the best underdogs since it’s so easy to make empathy for billions seem so evil and to make empathy for just one person seem so admirable. It’s also worth noting the cop-out taken at the end of the movie: since a true deontologist is incapable of killing bad guys (but we’re supposed to want Dr. Myrick to die at the end), Guy is attacked by one of Dr. Myrick’s bodyguards. During the attack, the gun accidentally fires twice, and Dr. Myrick is conveniently shot and killed. It’s like watching Spider-Man evade the Green Goblin’s last attempt to kill him, resulting in the Green Goblin’s death. In movies that favor the deontologist (especially movies for children), there is no need for deontologists to get their hands dirty – Satan is always there to murder the bad guy for them.

-

The three “precog” psychics who provide the Washington, D.C. Department of PreCrime with knowledge of murders before they occur. (from Minority Report) In the movie Minority Report, three “precogs” (mutated humans owned by the Washington, D.C. Department of PreCrime) are forced to predict crimes before they happen, and because of their high success rate, murder is literally eliminated from their city for the six years they work. When someone actually does try to commit murder on very rare occasion, they are caught before it happens. When it is finally publicly exposed that the future precogs see is not always the only possible future (and to make it worse, a government official exploited this fact to their own advantage in order to get away with murder), the entire Department of PreCrime is completely shut down before it can be implemented on a national scale. Never mind the fact that these very few false positives are far lower than the false positives we already accept in our current justice system. And as for enslaving the precogs, what about just asking the precogs to voluntarily come in and predict murders at random times during the week? And/or what about changing protocols so that when a crime is predicted, law enforcement waits until the crime is actually committed before arresting the perpetrator? At least in this case, nobody can complain, “I wasn’t really going to go through with it – I was only considering it!” Crime rates would still be extremely low since people would know they will be caught every time. These solutions all go flying out the window in favor of the heart-warming thinking of deontologists, who hold the freedom of three people whose faces we can see over the lives of thousands of dead people whose faces we cannot see.

Whether we romanticize deontology or misrepresent utilitarianism, the end result is the same. Most of us don’t give the warm feeling in our heart much thought, because we are happy that the protagonist was able to win playing with a set of rules that wouldn’t stand a chance in real life. We are taught over and over again that being 100% pure deontologist and 0% utilitarian is always the best choice. We ought to let the entire world perish as long as we did the right thing, because if we can’t behave up to some certain standard that deontologists arbitrarily define, the human race isn’t worth saving, yadda yadda yadda.

Pro-utilitarian movies are harder to find, but they’re out there:

-

Rorschach approaches Dr. Manhattan outside of Adrian’s arctic hideout (Watchmen). In the movie Watchmen, Adrian (super fast, super strong and super smart superhero-turned-billionaire) works with the ultimate superhero, Dr. Manhattan (who is able to manipulate matter) to create a self-sustaining energy source in a time of terrible world tension, on the brink of world nuclear war. In the end, Adrian manages to prevent Dr. Manhattan from seeing that the energy device is actually a bomb capable of mass destruction, and Adrian sets a bomb off in NYC, making it look like Dr. Manhattan did it. When Dr. Manhattan and other superheroes hunt Adrian down to squash him like a bug, Adrian turns on the news to reveal that the entire world has now united in a new peace in order to fight against Dr. Manhattan. Dr. Manhattan agrees that Adrian’s plan did achieve peace, even if the peace is based on a lie. The only way to save the billions of the world was to sacrifice a few million people with a bomb thought to be set off by the worst enemy the world could possibly imagine – an enemy powerful enough to squash an entire world with a single thought. Dr. Manhattan leaves Earth so that the sacrifice of millions will not be in vain, and only Rorschach refuses to go along with the lie (“Never compromise, even in the face of Armageddon”) and is killed by Dr. Manhattan before he can tell anyone his story. The classic argument against this kind of utilitarian sacrifice is to say, “But we don’t really know what the greatest possible good is for the greatest number of people. What if one of those people who died in NYC would have gone on to bring about world peace without setting off any bombs?” However, this movie presents us with a scenario where we can actually reject this argument, because both Adrian and Dr. Manhattan (who, in the end, neither condones nor condemns Adrian’s actions) are virtually gods in their combined knowledge, wisdom and intelligence. They do know.

-

Superman does not even flinch as his eyeball prepares to deflect a bullet. (Superman Returns) Superman, as portrayed in all his movies, is about as pure a deontologist as a superhero can get. He refuses to kill anyone, even those who plot to kill billions of innocent people. While the Superman movies may appear at first to be pro-deontology, I would strongly argue they work more in favor of the utilitarian argument, because it shows us that only Superman, with his nearly limitless abilities, is able to afford the luxury of applying such strict deontological philosophy into his real-world fights with crime and still be believable. Batman has equal reverence toward human life, but I find Batman to be far less realistic than Superman. It is easier for me to believe that an alien from outer space could deflect bullets with his eyeball than to believe that any person born on Earth could ever do what Batman does, even with unknown technology and billions of dollars to fund it.

Dexter: The Utilitarian Hero

[If you haven’t seen Dexter, do not read this! See the first two seasons of Dexter first, then come back and read this section.]

Showtime’s Dexter is a breath of fresh air for utilitarians like me who think about how utilitarianism is portrayed on television. Dexter is a captivating TV series about a serial killer (Dexter Morgan) who only kills serial killers who have already slipped through the criminal justice system via some lame technicality and who Dexter finds to be guilty beyond any doubt via hard physical evidence (whether the evidence is obtained legally or illegally). These killers also show damning evidence of intent to continue their killing patterns unless Dexter stops them. These criteria are all part of the “code” that Dexter’s legendary police officer father taught him to ensure that Dexter never kills an innocent. Dexter does make some mistakes along the way, but these mistakes are due to human error rather than flaws in his code, just as our own criminal justice system’s biggest flaw is that it us run by humans prone to error and susceptible to corruption (not to mention limitations of the system, such as limited capacity in prisons, how long it takes and how much money it costs for a trial to take place, or the number of guilty who go free).

What Dexter shows us is that people do not have to be morally “incorrect” to believe that what Dexter is doing is correct. You can say it’s “wrong” all you want, and yes, according to the law, it is. But proving Dexter is making the incorrect choice by killing those who would kill hundreds more? Good luck, because doing a wrong thing and doing an incorrect thing are two completely different concepts. Sometimes, doing the wrong thing is the correct thing to do.

Extreme deontologists are so prejudiced against this idea that many of them refuse to watch the show purely out of moral posturing. I wonder how many of these Dexter-rejecting deontologists have watched Silence of the Lambs, Se7en, any of the Saw movies, or any of the Jason or Freddy movies? I would love to find out why such people can stomach watching the downright evil serial killer who tortures and kills for pleasure, but can’t stomach watching the one who is trying to save innocent people from being murdered.

We can’t criticize Dexter’s code simply because it is imperfect, because the justice system is imperfect too. Of course, this relies upon the assumption that Dexter’s code saves far, far, FAR more lives than it costs, but this seems to be the case: sometimes his killing of just one sicko saves 30, 50 or 100 rapes/murders. Is it not a failure of our justice system when a serial rapist gets out after serving only a couple years in jail and rapes another 20 victims before getting caught again?

The main difference that deontologists focus on (or should focus on if they want their argument to sound more important than it really is) is the idea of social contract, which is what gives local, state and national laws (and the ruling government) authority that everyone is expected to respect. Certainly a country’s justice system put in place by the people has more legitimacy than a vigilante. Still, this has no bearing on the philosophical debate of whether Dexter’s actions are correct or not – it only gives society a legal reason to put Dexter in prison if he were ever caught.

Does this mean I should go out hunting for serial killers tomorrow? Absolutely not:

- My profession doesn’t give the the ideal access to all the tools and databases that Dexter has working at Miami Metro Homicide.

- Even if I did have that kind of access, I don’t have the stomach to kill people. I could barely stomach the dissecting of frogs in high school biology.

- I don’t have the means – I have not mastered martial arts, I have not studied the human body, I don’t own a boat for easy body disposal, I haven’t been trained by the police force’s best of the best, etc.

- There simply isn’t the abundant supply of extremely sick serial killers who’ve slipped through the system all conveniently located in Miami (or in any local area) as is the case in Dexter’s Miami.

- The evidence that Dexter is able to gather on people on his own is always so quick and easy to find, and it is always so thoroughly damning in showing the perpetrator’s guilt and intent to kill again. I don’t think this would happen in real life, so it would be magnitudes more difficult for one to apply Dexter’s code than is shown in the show.

But no matter. I think of Dexter as more of a thought experiment. In the universe where what Dexter does is actually possible, Dexter is taking the best possible course of action given his position, his abilities, his stomach for it, etc. The quiz in my part 1 post is a thought experiment too. Thought experiments are often more useful than real life for discovering exactly who we are.

Be sure to read the final part in this series, Utilitarianism and Deontology Part 3: The Wrongness-to-Goodness Ratio.

(c) 2013 Read Twedt

- Unless the scriptwriters are looking to win an Academy Award, in which case the scriptwriters should choose an ending that is either confusing or depressing. ↩

1 Comment